The blog home of Jeff Putz

Discouraged and excited, at the same time

posted by Jeff | Thursday, March 12, 2026, 6:40 PM | comments: 0These are weird times. When the Angi RIF went down at the start of the year, I kind of felt a sense of relief. I loved the job, felt good about doing it a few more years, but suddenly I didn't have to worry about any of the things. It's the kind of break you only get between jobs. So for the first month, I pursued just the leads I had through my network. One showed promise, one was clearly not for me, and four others ghosted me.

One month in, I started applying to all of the things, and trying to find humans behind the things, with limited success. Things have changed dramatically in four years, since I last looked. I'm pretty convinced that humans are less involved than ever, which seems like a pretty horrible way to go about hiring. I use the robots for a lot of different things, and it's stunning how much they get wrong. I wouldn't leave hiring to them. Regardless, it's discouraging.

At the same time, I get excited about the potential of everything. It could be a self-defense mechanism, masking anxiety in optimism. It's around everything, like what I could do, how I can spend all of this spare time, how I can set us up for empty nesting, etc. After the requisite morning job seeking, I've been pouring energy into TogetherLoop, and I'm the happiest I've been coding since building MLocker.

But I find myself tentative toward joy. Some of that is parenting, which is hard lately (always?). And I catch myself feeling like I don't have the time to be not experience joy, which is about as midlife as it gets. It's wild that even in this stage of life, I'm still looking for the same things I did as a teenager or college kid. Where do I fit? How do I define my value? Am I having positive impact on the world? Sometimes I don't like the answers I come up with.

I need a vacation from this. Fortunately I paid for one late last year.

Taking a breath on the Loop

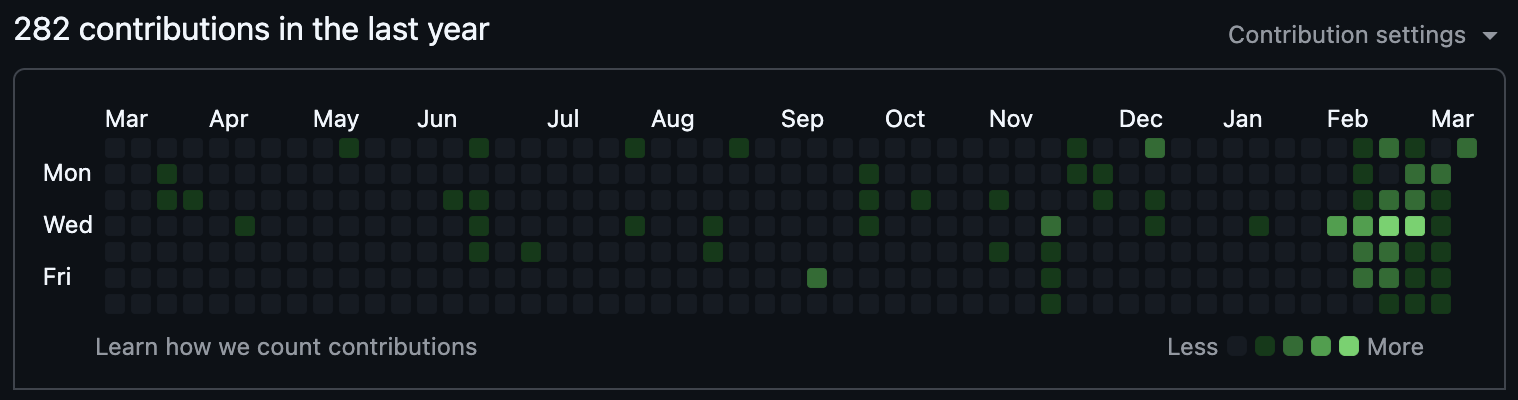

posted by Jeff | Sunday, March 8, 2026, 6:49 PM | comments: 0Since my colleagues and I got RIF'd about two months ago, I've been on a real tear working on TogetherLoop. I needed a project, and frankly the AI makes it a lot easier for a single human to crank stuff out. Since then, I've made about 200 commits and deployed about 60 times. It was pretty easy once I got all of that automation in place.

But while I have I think the most serious of bugs handled (which the AI sucks at, but that's another post), I need to just let it sit for awhile, and actually use it. That's tricky, because what I really need is other people to use it so there's something to interact with. And that's weird because the whole point of the app is not to drive engagement, just record what you want, read what you want, and get out.

I've been out in the world making posts to it, and it seems to work pretty well. I need to get the video figured out still, in a way that won't cost me a ton of money. That'd be less of an issue if a certain phone maker defaulted to the same standards that everyone else uses.

So the plan is to fix anything serious, but otherwise just use the thing. And look at my activity graph!

Let's see what happens next with TogetherLoop

posted by Jeff | Thursday, March 5, 2026, 1:52 PM | comments: 0Well, after a week or two of bug fixing and tweaking, I think TogetherLoop is good enough to put it in front of people.

This is a weird thing to build, because it's value isn't tied to the quality of the code or design, it's tied to the volume of people who use it. More specifically, it's tied to the number of people in your circle of friends that use it. To that end, I don't think reaching people to try it is the challenge, it's getting them to invite others.

I'm still messing around with video. The trick is finding an economical way to transcode video without having to provision a bunch of infrastructure. I won't get into all of the technical reasons that it's challenging, but I'm being careful because right now I don't have to spend anything extra over what I'm already using. Well, that's not true. I'm paying for a CDN to load the app itself. I'm not certain that I'll keep that, because I'm not convinced it's really any faster.

It's fun to actually ship something new on my own. I've had all of these projects sitting around unfinished, and I self-loathe for all of the undoneness.

How to work with AI... this sounds familiar

posted by Jeff | Monday, March 2, 2026, 10:11 AM | comments: 0In between countless posts about AI that could be summarized as, "You're doing it wrong" (boring!), there are folks making genuine efforts to find the best way to work with the tools. And the truth is that you've seen this before.

On one end, there are people coming up with frameworks and tooling to give the AI what it needs to get their coding output right. These come in variations on specs, detailed requirements, and most importantly, outcomes. They try their best to account for edge cases, too. At the other end, you've got the vibe-coding, surrender to the robots and go for it crowd. They get something that kind of works pretty quickly, but requires a lot of iterating to get something production-ready.

You're probably already seeing where this is going. These are parallels to waterfall and agile methodologies. It's not a perfect comparison, but there are similarities. Also not surprising, the former lends itself to product leader thinking, while the latter is engineer biased. This arrangement should raise an eyebrow about what AI is, and what it's truly capable of. Let me get back to that.

In the pre-AI world, we navigated this world already. Waterfall never really delivered on the intended quality outcomes, and took too long. It was built on assumptions that didn't account for the way that users actually interacted with the software. Agile is a good idea that has been hopelessly corrupted by associating it with tools and artifacts, ignoring what the Agile Manifesto said, "Individuals and actions over processes and tools." For those of us who have enjoyed working with productive teams, we know that being iterative with the right amount of context is the sweet spot. Build as little as you can, challenge your assumptions, repeat, and you're at the right spot when the stakeholders are happy with the outcomes.

We're going through the same journey we did without AI, and applying it to the AI. We're so convinced of its human-like interaction that we just have to apply what we already know. Is this an accurate assessment? Again, remember that AI does not have judgment, creativity, and it annoyingly doesn't ask questions very often. But these two approaches do have similar outcomes, with the same pros and cons. The anthropomorphizing of the AI in this case seems to be appropriate.

It also shines a light on what I've been saying all along: AI-assisted coding is faster in the hands of an experienced software engineer, but the coding was never the hard or time consuming part of making software (just the most expensive part). It doesn't eliminate the need to decide what to build, and why, which is what you have undoubtedly spent many meetings discussing.

So save your anecdotes about the one guy who built a social network in a few weeks (that's me!), or the one that built a compiler surrounded by an enormous existing test suite. Those aren't typical. AI makes coding more fun and productive, sure, but that's the smallest part of the process.

Making notifications work in TogetherLoop

posted by Jeff | Thursday, February 26, 2026, 3:43 PM | comments: 0I've been working a bit harder on TogetherLoop, my social network. As I've said before, I don't know if it's a business, and right now that's not the point. Once I got the basics in place, I decided to tackle notifications. It's not my first time tackling something like this, as I implemented something similar in POP Forums a few years ago.

It's a pretty classic example of doing asynchronous, distributed work. When someone makes a like or a comment, the system shouldn't be hanging out and doing all of the work while the user waits. So it fires off a message to a queue saying that the event happened, and an Azure Function ("serverless") handles it. That function saves all of the data about the notification, and figures out who needs to see it. This is the part where the user can't wait for the work, which is why it happens in the background. If a hundred people need to be notified about a comment, it has to generate a hundred notifications, and then send each one.

The notification hits a Redis topic, where the backend API happens to be listening. That backend then uses a websocket connection to send each notification to the owning user, assuming that they're even online. That's a lot of bouncing around, but it pretty reliably delivers the notifications without bogging down the user.

Incidentally, I did try to have the AI design something, but even when I suggested that it should be an async process, it suggested a lot of patterns that were not particularly robust, or would be slow. But when I scaffolded everything out, using comments as pseudocode, it did things almost exactly as I wanted.

The LinkedIn algorithm is broken

posted by Jeff | Wednesday, February 25, 2026, 9:58 AM | comments: 0You know how Facebook lost all its utility when it stopped being about your friends and turned into all ads and engagement bait? LinkedIn seems to be going the same way.

Fake recruiters are bad enough (I report them almost daily), but it's now promoting the worst of the AI hyperbole and fake expertise. If I'm just scrolling the home page, about 3 in 5 posts are by random people with "CEO" or "founder" in their title, appended by AI something something, each declaring that something is dead, something is killing something else, you should have FOMO, the end is near or something else that's ridiculous. Especially when it comes to AI, these cats haven't been using it any longer than the rest of us, so what makes them qualified to know anything?

And I know the algorithm is broken, because I've gamed it myself. In the last six weeks, my posts have collectively seen about 250k views. The Internets say that's "viral" by LinkedIn standards. I hit those views because I carefully worded my posts with the right keywords, while I commented on the right posts.

(It's worth mentioning that all of this exposure has not, in fact, landed me a new job, so I wouldn't say that I'm "winning.")

AI tooling has made coding fun again for this engineering manager, and my side project, the social app, had made me confident in its use. And while a lot of energy is being expended figuring out the best way to use the tech, the outcome, working software, seems to be an afterthought. While coding accounts for a disproportionate cost of product development, the practice itself is a fairly small part of that development. It was never the biggest part.

Humans are still required. AI cannot create novel design, it cannot innovate. It has no judgment. Left unsupervised, it generates code that will not scale and is not secure. Think about what an LLM is. It's an algorithm that finds patterns, trained on patterns it finds on the public Internet. While there's some good code on the Internet, most of it is bad. If you don't have the experience to tell it what good looks like, it will mimic what it knows.

So if you encounter AI "influencers" on the LinkedIn. Dislike, keep scrolling. It's mostly noise. If you're a business leader, don't buy what they're selling.

The anthropomorphization of AI

posted by Jeff | Sunday, February 22, 2026, 3:00 PM | comments: 0One of the frightening things about AI chat bots is that, because they "speak" in normal language, people mistake them for being sentient and human. People have allowed the machines to talk them into divorce, suicide and violence. They also turn racist pretty fast, and that sure seems human-like.

I was slinging code last night, which is to say that I was prompting Claude to sling code. It made a change that caused the bits to stop working, so I asked it to dig into why. It found the problem, and then caught and ate the exception. I thought that it was generally pretty well understood, by humans at least, that this is the greatest of sins. You just don't eat exceptions. Of course AI tech bros will tell you that you have to direct the AI to debug, but this was its solution to debugging. I'm sure this happens all of the time for non-engineering types who vibe code.

My first reaction was in the vein of, "You moron, you can't do this." But I quickly caught myself to realize that I was anthropomorphizing the machine myself. I can't hurt its feelings, though for some reason belittling it felt satisfying.

As fantastic as these tools are, and as promising as they (maybe) are, we have to keep in mind that expertise is not easily acquired. It's not any easier to train the robots, either, since they can't determine right from wrong. We can have "right" people train them, sure, but when that experience leaves the workforce, who trains them? This seems like a larger cultural problem right now, where we have stopped valuing expertise. Like, expertise for everything. Folks think they have a PhD in Googling now, which feels like we're moving toward the movie Idiocracy.

Randos on LinkedIn, who have been using AI as long as the rest of us, seem to be making it worse by promising to crack some code for you, despite having no history of delivery. It scares me that business leaders take these folks seriously.

So let's all take a breath, stop equating machines with humans, and leverage them as the tools that they are.

"Quintessential America," not what you think it is

posted by Jeff | Thursday, February 19, 2026, 11:36 PM | comments: 0I saw a bunch of videos of talking heads complaining about the Super Bowl half-time show, which by the way was watched by over 120 million people. They took issue with a performer who put on a joyful show that was entirely in Spanish. Megyn Kelly had a particularly vile take on it saying how it shouldn't have been "just for the Latinos" (with offensive accent), and that the Super Bowl is a "quintessentially American" event.

I don't think it's just me, that she doesn't know what "quintessentially American means."

First, the non-subtle subtext. The implication is that anything that isn't white people in English is "un-American." Does anyone really have to point out that we've been a nation of immigrants literally from the start? Does she really mean to say that if ain't straight, white, self-labeled "Christians" that it isn't American? What a dumb way to look at our nation, especially when you consider that white people are getting close to being a minority-majority (57%-ish, at last count). White nationalism is not a good look.

The funny thing is that, our founding leaders were mostly white men, but their general m.o. was to not allow a government that discriminated against people. Well, unless they were slaves, but by the Civil War, we can generally say that they came around, even if we still haven't gotten over that. A lot of what they espoused was equality, even if they didn't always follow through. But they did codify it in many ways, and we've slowly augmented that ethos since then.

Here's what I don't get... why is this subculture of white people so afraid to be exposed to culture and ideas that don't fit in their little box of what they think America should be? Why should they even get to decide? It wasn't that long ago that they railed against "liberal snowflakes" that needed "safe spaces" or whatever, to avoid things that made them uncomfortable. Now they're the snowflakes who can't be bothered with scary people of color that like different things and that have various cultures different from their own. And you know, there is no official "culture" in the United States. We can identify with whomever we want, believe in whomever we want, or believe in nothing, if that's your thing. You don't get to choose that for others.

My kid and I were seeing his therapist, who is of Cuban descent, about the opportunities he's had to know various kids born here, but who were one generation removed from any number of places. Latinos of course are the dominant group here in Florida, but also South-Asians, East-Asians, Arabs, Eastern Europeans, and even a few Africans. On vacation, he's met cruise staff from dozens of countries. He indicated that he finds them interesting, for their differences. I point that out because he doesn't feel threatened by those differences.

Grown-ups could learn a lot from kids.

The glasses you'll never see me wear

posted by Jeff | Wednesday, February 18, 2026, 11:17 PM | comments: 0I wrote about my first eye exam, which overall was a fairly pleasant experience. I mean, the upside is that my sight is actually not horrible for my age. It's just that inside-arm's-length to deal with, but especially later in the day. So once I got the new glasses, a 0.25 diopter affair, I was excited at the difference they made when I was doing NYT puzzles on my phone before bed. But the enthusiasm somewhat turned to frustration.

The obvious thing is that I can't see anything further than arm's length from me while wearing them, which I expected. What I didn't realize is how, even at such a low correction rate, everything else is so blurry. In practice, if I need to see anything I'm not holding, I end up Chuck Schumer-ing them, always looking over the top. Or if I get up, I have to just take them off. Maybe a better analogy is Sally in When Harry Met Sally, though she's got the old-lady string, hanging off of her neck. It's just such a specific use case that also happens to interfere with every other possible use case. That annoys me.

The other thing is that if I'm working on my laptop, most of the day I can see it fine, and in lap or table situations, there's no problem. Ditto for my desktop, which involves 24" screens that are plenty far away. But then there's another bedtime situation. My eyes are tired enough that normal distance isn't intolerable, but it would benefit from a little correction. To be fair, the doctor warned me about this, but I already find it challenging to have a thing on my face for any length of time (it might be an autism thing, I hate sunglasses too), so I asked to stick with the primary use. But it means that in those late hours, I need to bring the machine closer to me with the glasses, which bunches up my arms and it's just awkward.

The biggest problem though is that, if the lights are on in the room, my eyes are still trying to account for my peripheral vision, meaning they're trying to bring that into focus. This gives me headaches and I have to bail. If the lights are off and it's just my screen surrounded by darkness, there's no problem.

So I'm in a place where I love how well I can see again, in that short range at night, but annoyed at all of the situations around it. I'm being slightly dramatic, because I'm learning to adapt. It's just angst that I have to adapt at all. It might be the universe telling me to stop with the screens at night.

Our photo book was small this year

posted by Jeff | Sunday, February 15, 2026, 11:23 AM | comments: 0Since 2018, I've been making these Google photo books. It's fun because they're uniformly 7 inches square, fit well on the coffee table, and make for a little conversation piece when people visit. The last few years have been pretty large. In 2024, we went to DC, and vacationed with another family to DCL's new spot in the Bahamas. The year before that was Northern Europe. In 2022, basically everyone we knew visited Orlando, while we opened Steinmetz Hall, the Wish and I met Ken in Cleveland for Cedar Point. Obviously 2021 involved getting back to normal life.

But the 2025 book is pretty slim. We didn't take any big trips outside of the usual cruises, though the Treasure was a new ship. We did our "Coronado crawl" a few times, but we know what that resort looks like, so not a lot of photos. We saw a lot of shows, but at best we just have our pre-show selfie. We didn't really plan it this way, though there were other factors at play. Parenting was extra hard, and so I guess we were weary of taking any big travel swings. Losing Finn in the spring unexpectedly kind of left a cloud over everything. Everything just felt uncertain. So we played it safe.

I suppose the upside is that all the money we didn't spend on travel was saved, which makes this whole unemployment situation a little easier. But now as we're a month and a half into this year, I'm starting to wonder if this year will be any different. There was a time when we planned to visit Iceland for the next full eclipse, but I don't think that's going to happen. We have two cruises that are already paid for. But if you ask me where I'd like to go, with less than six months to plan for it, I just don't know.

Introducing Loki and Thor

posted by Jeff | Wednesday, February 11, 2026, 6:15 PM | comments: 0I just realized that I haven't written about our kittens. We adopted a couple of little guys, named Loki and Thor. Thor is the smaller of the two, which is hilarious to me. He came to use with a little mark on his nose, apparently a reaction to some medication, but it's mostly healed now.

I was pretty sad that we couldn't keep the girls we had in December. They were just too hostile toward Poe and Remy. These guys are the opposite, in that they follow the older boys around and desperately want to be friends, cuddle and play. Remy isn't really having it, but Poe is starting to take on some daddy vibes. Remy didn't even get along with the ragdolls, and they were here when he arrived. So I guess there was no point in waiting for him to like other cats, just wait for cats that get along with them. So here we are.

Loki gets up in your business and forcefully tries to get his head under your hands. He drools a lot in the process, like, dripping from his mouth. It's so weird. He's also kind of a troublemaker, always getting into stuff. He chases Remy around relentlessly. But when it's time to finally sleep, he'll curl up next to you and pass out. We're pretty sure that he's gonna be a big cat.

Thor is kind of a runt, but also eats like there's no tomorrow. He follows me around a lot, and just wants to be near people. He purrs non-stop, when he's eating, falling asleep near you, whatever. It doesn't stop. He has a tendency to plop down on your chest, if you let it happen. Very much a cuddler.

They sleep together quite a bit, but not always. Again, they really like the adult cats, and Poe seems willing to give them a shot, most of the time. If you're into lap cats, that's what they are. Hard to say if they'll always be that way, but for now they are definitely furry buddies.

There has been a lot of stress in our house for the last month or so, but these little guys help reduce that to a degree. We've also doubled our litter robot count, so there's no shitter scraping anymore.

Top five pros and cons of AI agentic coding

posted by Jeff | Wednesday, February 11, 2026, 10:15 AM | comments: 0Yes, I've devolved into writing listicles. Regardless, these thoughts and themes have been running rampant in my brain, and this will help purge them. So indulge me, for a moment.

The pros...

5: Release from syntax burdens. This is a huge win. I prefer C#, and with the changes that come every year, I don't always know what the most elegant way to write something is. Also, I often forget how to use delegates and events, but the machine can get it right the first time.

4: Import expertise that you don't have. First time needing to use that library, or even that language? The AI's got you covered. It even works figuring out build YAML and such.

3: Pairing partner that works for cheap. Pairing interactions go pretty well, you just have to keep prompting it to get where you know it has to be. It's like working with a junior developer, driving at the keyboard while you discuss things.

2: No documentation hunting. There's always a library or framework that has some feature that I don't understand. Now I don't have to go find the docs, I can just ask the robot.

1: Types faster than you can. This is especially true when you're working on something solo, and not on a team or in an enterprise. You know what good looks like, and you can describe it, go get an energy drink, and come back to exactly what you wanted.

The cons...

5: You have to trust and verify. I don't think this avoidable. You have to check the robot's work to make sure it isn't doing things that are security risks, or performance issues-in-waiting.

4: Coding isn't your biggest problem in the first place. I've been harping on this for weeks. It can generate code fast, yes, but coding by many estimates is 10-20% of the time spent in product development. The creativity and product requirements are the genesis of innovation. AI can't do that.

3: Trained on crappy code. Let's be realistic, most code in the wild isn't great, and that's what the robots trained on. So it's unsurprising when the machine comes up with some ugly code smells, like a nullable boolean. Why does it believe that a boolean with three states is a good idea?

2: Overconfidence. While this is better than it was a year ago, I'm surprised when it generates something that won't even build. When you tell it what to fix, it high fives you and congratulates you on being right. But it was so sure in the first place! Now put this in the hands of vibers, like lawyers or product managers, who don't know what to look for, and you've got trouble.

1: AI lacks context. It doesn't know what it doesn't know. For example, if a user should match the owner of a record fetched by an API, it doesn't know to check that unless you tell it to. Looping back to #4, so much time is spent describing the outcomes that you're after, whether you're a human developer or a machine.

Again, it's a fantastic tool that makes the work better, definitely more fun, but the hype is completely overblown. Software engineers enthusiastically love it, as they should, but a lot of leaders keep making benefit claims that aren't backed up by deep, peer-reviewed studies. Our time as leaders would be better spent figuring out how best to use this magical thing in a way that keeps advocating for better developers, because they're not going to be replaced. The anecdotes produced are usually special cases that don't reflect real-world development in the enterprise. As a reminder, that's typically aging code bases written by people who moved on years ago and left little to no documentation. AI can't supernaturally acquire the context that humans can't.

Let's stop treating the tool like a panacea, and work on figuring out how best to leverage it in real situations.

Coding was never the struggle part of software

posted by Jeff | Monday, February 9, 2026, 10:15 AM | comments: 0People thought my recent post about AI was simultaneously taking a fanboy position, as well as a poopy-pants skeptic position. So let me reiterate what I really meant: I think that it's a fantastic tool for developers, but coding was never the bottleneck in shipping software. Folks immediately jumped in to say "I get 10x productivity" as well as "It's all overstated." I was saying that the impact to the business was not what you think.

A retired business leader that I greatly admire (theme park nerds know) recently said that, "If you are in the hospitality business remember some meetings are more important than others," above an AI cartoon photo of him meeting kids at a theme park. Obviously he was pointing out that we need reminders that the things that influence and move the needle for the business are often not the things that we think. That's where I meant to go with that AI post.

While I continue to call for better data about AI impact on coding in a business context, instead of a developer context (hammer/nail problem), I'll offer my anecdote. Right before people really got into agentic coding, my most recent team shipped a great service, in production, in about two weeks. Sure, we were doing a gradual rollout, but we got to that point by ruthlessly limiting scope, challenging assumptions and getting to the core of the problem that we were trying to solve. Productivity was increased by those means. Two weeks later, user feedback suggested that we got it very wrong (by we, I mean my engineering team and product team). That was totally OK though, we pivoted and did something that delivered a ton of value. Over the next year we tweaked performance and observability, and discovered a bunch of edge cases that we had to account for.

Going back to that first iteration though, two weeks was a huge win. I was so proud of the team. We got it wrong, but our process of shipping and then adapting was so fast. The truth is that agentic coding would not have changed that outcome. Coding was never the bottleneck. Making a product, and innovating, requires user feedback and human judgment and wisdom. The robots can't do that yet, if they ever can.

Software engineering is so much more than coding. Product development is so much more than coding. If you want to eke out productivity gains, sure, AI tooling will help, but the bigger wins will always come from the process that includes your stakeholders, users and product partners. We can't frame productivity in coding alone. We must frame it in terms of outcomes and the overall process.

Are you curious or an alpha dev?

posted by Jeff | Thursday, February 5, 2026, 10:14 AM | comments: 0From a LinkedIn post I made...

My AI post yesterday blew up, in no small part because some folks didn't like what I had to say, or at least, didn't agree with it. That's cool, I enjoy some spirited debates. I stand by my statement that there isn't serious academic research about efficiencies gained, and no one really provided any. AI is very exciting, and a game changer, absolutely, but I don't think it's in the ways people claim. To be continued, certainly.

What I find fascinating about the discussion is how so many people are confident that their position is correct. Everyone has "AI" in their LinkedIn title (some funnier than others, wink), but who is really an expert? Two years ago, it was largely a novelty, according to surveys, and now everyone uses but doesn't entirely trust it, in the same surveys. Expertise, to me, means you've been doing something for many years, and as such, AI is the new blockchain. Remember when everyone had that in their profile title?

Putting aside AI for the moment, and seeing as how this is a social network for professional development and employment, I think it's important to consider how you present yourself. While expressing confidence and demonstrating knowledge is essential, it's equally important to show curiosity and humility. It's the difference between being curious and being an alpha dev.

A lack of curiosity, or even a sense of wonder, is to me an essential part of maturing, at any age. Culturally and politically, it seems like a lot of people lack curiosity, and that hasn't been good for society. A Google search combined with selection bias is not curiosity. It's certainly not critical thinking. When we double-down with certainty in the face of new information (or avoid the information entirely), we cease to be curious.

In software engineering terms, this manifests itself as the classic alpha dev. For these folks, it's not just important to be right, it's important to assert your correctness over others, and maybe even belittle them. Nobody likes those people, and we've all worked with them.

I admit that I can fall into this pattern, to an extent, but where I hope that I'm different is that I'm arguing for nuance. I am immediately skeptical of anyone who believes that they have The One Right Thing in any situation. People, companies, circumstances are different. Leadership involves understanding the nuance and tailoring the process to the scenario. One size rarely fits all.

So be curious, consider new information, and above all, leave room for nuance. To achieve the outcomes that you're after, be ready to accept that you may have been after the wrong outcomes.

Productive coding

posted by Jeff | Wednesday, February 4, 2026, 10:08 PM | comments: 0I spent some time making AI write code for me today. I ran out of usage credits at one point, but they reset at 6 p.m. Where I find it works really well is when you build a few features in layers, showing what your conventions are in terms of structure. Once you have that, you can refer to those conventions, or codify them in your CLAUDE file, and then ask it to take bigger swings. On those big swings that take a few minutes, I lose though, because my ADHD can't take those sorts of breaks. I'll figure that out, hopefully.

All of this productivity happens because it's greenfield work. If I had to throw it at some of the monolithic nonsense I've encountered at various jobs, it would be less useful. Or at least, you would spend more time verifying things and writing tests (if that's even possible) instead of typing, which honestly is also good if you're trying to understand what it's doing. But everyone on LinkedIn is selling some reason that AI makes people "10x" or whatever, though they have only anecdotes to "prove" it. There hasn't been a lot of significant academic study about it, but what there has been tracks no to negative movement in productivity. Of course the folks selling something (or themselves) will tell you that you're doing it wrong. And hey, I've got another popular post about it. Tech bros don't like to be challenged.

Every time that I sit down and work with the robot, I'm still amazed, because it's like magic. Since I don't code for work, and it's more in streaks with my own projects, I tend to forget a lot about how a library or framework works. The machine is great at reminding me, explaining stuff and especially getting into things way outside of my knowledge.

AI will help people write better code, for sure, and somewhat faster, as folks understand how to direct it. In that latest LinkedIn post though, I point out that the coding part is relatively small in terms of what a developer does all day. It's not the force multiplier that people make it out to be. Or at least, there isn't data to support that claim.

Stupid copyright trolls

posted by Jeff | Wednesday, February 4, 2026, 1:19 PM | comments: 0There's a company out there, that I'm not even going to name, that scans the Internet looking for images that their clients claim a copyright on. When they find them, they send messages to the site owner and demand money from them. This is technically legal, even though it borders on extortion and harassment. A lot of people pay the money.

I'm not one of those people though. I got two such messages today, regarding forum posts. As any idiot with a web site knows, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, for all of its flaws, has a safe harbor provision for site operators that host user-generated content. So I essentially told them to go fuck themselves and read the law, in which case they indicated that the messages were automated, sorry, our bad.

They're a known copyright troll, and they do sometimes bend legal ethics and send lawyers after people. That would be a real waste of time for my LLC, because it doesn't have any money, even if the law was on their side.

Am I a LinkedIn... influencer?

posted by Jeff | Tuesday, February 3, 2026, 10:32 PM | comments: 0Ugh, I'm generally pretty down on social media, and don't worry, it looks like spammers and algorithms are going to ruin the professional network in the long run too. But somehow, in the last month, I'm getting what the Internets consider "viral" attention, which is a pretty low bar for LinkedIn. I suspect my usage of it will practically stop if I can land a job, but for now, I don't mind the attention... if it helps.

At the four-week mark of non-employment, I've had a total of four leads, and various levels of discussion and interviews. One was a series of red flags that I politely declined further involvement, one was a good second interview that I was pretty excited about, but didn't get it, and two are still up in the air. What I have not done is blindly submit to jobs without knowing someone on the inside. I did this early last year, when I went through a brief period of wanting to do something else, and after 200-ish applications, it didn't go anywhere. So I'm sticking to what I can control. All of the above were initiated through my network. Two came to me, instead of me to them, through a contact.

A Google search says that "good" action on your posts starts around 1,000 views, or maybe 3,000, in some cases. Well, a post that I made late last year about QA is at 100,000 views, and counting. The follow-up is around 30,000. My post about getting booted from Facebook is over 35,000 so far. Just this month, my posts about getting RIF'd, what to do after getting RIF'd, and what to put on your resume, are all tracking for 20,000 so far. The rest made this month have been around 3,000 each, including one from yesterday that still has some momentum.

Apparently this isn't typical. Cool, but what do I win? I've had hundreds of profile views, some categorized as blurry-icon recruiters that I can learn the identities of if I pay for premium. It's hard to measure what the value of this is. I don't have a new job yet, so I'm not sure that it's particularly useful. But again, when I compare to my effort last year, I've had 100% more interview action than before, which was none.

What's already exhausting is that everyone has a hot take about AI that isn't rooted in any data or study. And yes, coding with AI agents is way more fun and takes a lot of the tediousness out of it, but it doesn't mean that it doesn't still require your expertise. I have more opinions on that, but I guess that'll be a future post. Maybe it'll get 100k views, too.

Your job and your identity

posted by Jeff | Monday, February 2, 2026, 2:45 PM | comments: 0I imagine that one of the most jarring things about getting laid-off is that you no longer get up in the morning for the same reasons. Your "job" becomes looking for a job, with all of the rejection and judgment that seems to come with it. I'm sure that none of that is particularly good for your mental health.

Still, it's not unreasonable that we derive some amount of our identity from what we do. That makes sense, since we spend 40 of our waking hours doing the thing. There are at least two variables that I can think of that influence the level to which we identify with our work. The first is tenure, or how long we've worked at a particular place. That's certainly what I struggle with right now, because four years is a long time to spend with folks (why four years is "long" in tech deserves its own discussion). The other thing is the outcomes that we associate with the work. For makers, especially artists, this can totally throw the identity balance out of whack. If you're an actor, stage manager, musician, you're involved in things that deeply affect others.

Take all of that away, and suddenly you may find yourself lost during the day. That's OK. The outcomes may be thrilling, depending on what your line of work is, but really it's the people that make it special. As they say, when you're on deathbed, it won't be the work or the money that you remember, it'll be the people. To that end, especially if you're part of a large RIF, you have instant community. That's a good place to spend your time.

Something my therapists asks is, "If you could be doing anything right now, what would it be?" The truth is I don't know, and that's scary. My best shot is to continue doing the kind of work I did, as an engineering leader, but could I (or should I) be doing something else? Don't afraid to be bored, because it might lead you to new places.

Cold incompatibility

posted by Jeff | Sunday, February 1, 2026, 1:26 PM | comments: 0I can confirm that with the temperature getting down into the 20's here in the greater Orange County area, that I am incompatible with cold. I do not care for it.

I woke up to a nasty surprise, because it was down to 65 indoors, which might as well be freezing for me. It turns out that these newer Nest thermostats have a setting in which it uses "alternate heat" below a certain threshold outside, which defaulted to 35. I don't know what that's supposed to do, but it meant that the heat pumps were not engaged, and the two units together were pulling like 10 kW doing nothing. When I got up at 8, we had already used 80 kWh of electricity, when a typical day is at worst 60 kWh all day, charging both cars. I changed the setting and it went back to heating properly. In fact, the heat pumps are actually pretty efficient, more so heating than cooling. The upstairs unit, which we replaced about a year ago, is two-stage and runs pretty low for heating and cooling.

HVAC aside, I find my body reverting to my Ohio ways in the cold. I want to hibernate, even when the sun is out. I just want to lay around.

On the plus side, it'll be 50 degrees warmer on Wednesday.

My first eye exam

posted by Jeff | Monday, January 26, 2026, 3:11 PM | comments: 0I saw an eye doctor today, for the first time ever. That's surprising because my parents both had glasses at a young age, so I somehow dodged that bullet.

Presbyopia, which typically sets in for most people in their early 40's, has been a problem for me for probably more than a year at this point. But also, it's unusual that I avoided it for so long, as it's considered a normal part of aging. Basically, my minimum focal distance increases throughout the day as my eyes tire. My distance vision is totally fine, 20/20. While I can hold my phone at a normal distance in the morning, by evening I need it about as far away as my arm will allow. In recent months, that's become more annoying, so I figured now's the time to do something about it. I only need a quarter [whatever the unit is] of correction, so even then, that's not bad.

Technology sure has come a long way though. Insurance won't cover it, but they have a machine now that can image the back of your eye in extreme detail, without having to dilate or any of the uncomfortable nonsense. They can even measure the pressure of your eyeball from a distance. Even measuring your head for glasses is done with little green dots clamped to a frame, and a tablet app. We live in the future.

Without employment, my eyes are getting a break from looking at screens all day, though that has never been a particular issue. I'm not doom scrolling either, having mostly reduced my social app use to checking Instagram twice a day. I'm still fairly addicted to the NYT Games, and like to read up on Ars Technica, but that's about it.

Middle age is so weird. I mean, technically your body starts to decline after your mid-20's, so this is hardly surprising. Hopefully the rest of me is continues to beat the odds until I'm good and old.